Despite significant advances in AI policy development, implementation across Africa remains fragmented and weakly accountable. This piece examines the institutional and governance bottlenecks behind this gap. It advances an Africa-centered approach to AI ethics and accountability grounded in local values and institutional realities.

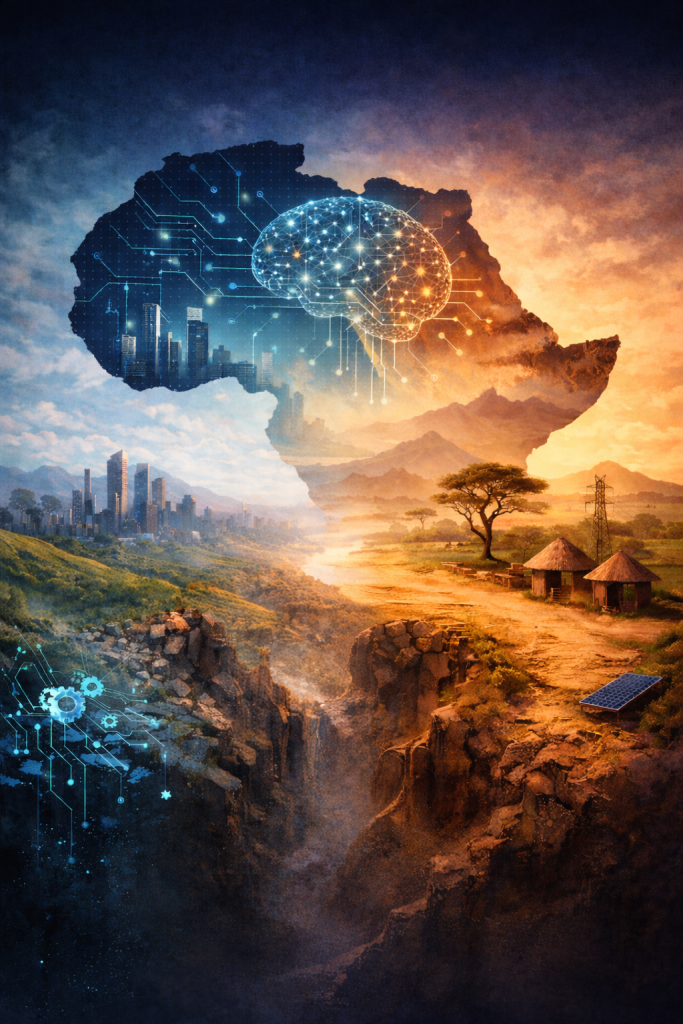

Africa stands at a critical inflection point in its technological history. The continent’s leaders have articulated an ambitious vision: positioning Africa not as a consumer of AI technologies, but as an architect of its own digital future, a vision encapsulated in the call for “AI for Africa by Africa.” Yet between the inaugural Global AI Summit in Kigali on Africa, held in Kigali on 3-4 April 2025, and late 2025, a troubling pattern has crystallized: the gap between policy ambition and institutional implementation is widening dangerously. While over half of African governments have drafted national AI strategies, only a fraction have attached meaningful budgets, legal frameworks, or monitoring mechanisms to translate their vision into reality.

This analysis examines the structural barriers preventing Africa’s AI strategies from yielding functional governance and proposes targeted interventions grounded in institutional realities across the continent.

AFRICA’S AI POLICY PROGRESS: GENUINE MOMENTUM, FRAGILE FOUNDATION

Africa’s recent policy achievements are substantial. In July 2024, the African Union adopted its Continental AI Strategy, a landmark document providing strategic direction across fifteen areas and calling for member states to align national frameworks with Agenda 2063. This catalyzed remarkable momentum through 2025, with countries including Ethiopia, Nigeria, Zambia, and Côte d’Ivoire publishing national strategies. Kenya’s 2025-2030 National AI Strategy stands out as particularly comprehensive, explicitly integrating ethical, inclusive, and innovation-driven pillars while dedicating significant fiscal resources to implementation. Similarly, Egypt and Ethiopia have scored highly in recent assessments for tying AI policy directly to national development continuity and establishing strong institutional anchors. Yet this policy progress masks a critical weakness: institutional capacity. Research examining 20 African countries reveals uneven progress across governance, financing, and ethics. The verdict is stark: many strategies remain invisible to the public, lacking dedicated multi-year budgets. Most depend on donor support or general Information and Communication Technology (ICT) allocations easily diverted to other priorities. This financial fragility undermines long-term sustainability.

THE IMPLEMENTATION CRISIS: THREE SYSTEMATIC FAILURES

1. Institutional Fragmentation Without Coordination

Africa’s AI strategies typically reside within single ministries, often Communications or Science and Technology. Yet AI’s societal impact spans health, agriculture, finance, and justice. Without statutory inter-ministerial coordination, each sector develops AI applications independently, resulting in fragmented standards and chaotic data governance.

A health ministry may enforce algorithmic transparency for diagnostics, while a finance ministry adopts different standards for credit-scoring. This allows vendors to exploit inconsistencies and prevents the development of continent-wide best practices. Furthermore, while the AU Data Policy Framework provides strategic direction on data sovereignty, national implementation remains siloed. This complicates the development of federated learning infrastructure that could benefit multiple sectors.

Recommendation: African governments must establish statutory AI Governance Councils with authority to harmonize standards across ministries. Kenya’s approach of centralizing AI strategy within its national development agenda offers a partial template, but functional governance requires extending this integration horizontally across sectors.

2. Capacity-Expertise Mismatch

Countries across Africa face an acute capacity deficit. Regulators trained in administrative law often struggle to evaluate vendor claims about algorithmic fairness or model interpretability. Central bankers often operate without dedicated frameworks to audit AI-driven credit scoring for bias, while healthcare regulators face technical constraints in validating diagnostic systems.

This creates a perilous dynamic where policymakers either approve AI applications they do not understand or block them preemptively. For instance, while Nigeria has demonstrated grassroots innovation through local-language AI models, the ecosystem remains hampered by inadequate statutory backing for technical regulators.

Recommendation: Nations should establish AI Governance Institutes within research universities to develop sector-specific standards and deploy technical fellows into government ministries. This “revolving door” model builds regulatory capacity while maintaining technical currency.

3. Data Governance and Sovereignty

Strategies deployed across Africa often discuss transparency but overlook the foundational problem: data quality and sovereignty. Agriculture, the continent’s largest employer, lacks systematic, digitized datasets on soil and weather, forcing reliance on imported models that may not generalize to African contexts.

Simultaneously, without clear data rights, African nations risk extractive partnerships where foreign companies access health or financial data in exchange for services, a digital echo of historical resource extraction. The AU has prioritized data sovereignty, yet regulatory bodies capable of enforcing data residency and auditing cross-border flows remain underdeveloped.

Recommendation: Governments must co-invest in public AI infrastructure, including federated learning networks that enable collaboration without centralizing sensitive data, and open-source data repositories for African contexts (e.g., local crop profiles, disease datasets).

TOWARD ACCOUNTABLE GOVERNANCE

To move from ambition to accountability, African nations should prioritize three interventions:

- Embed Accountability in Procurement: Government contracts for AI systems must mandate algorithmic transparency reports and regular bias audits. Vendors should explain training data origins and known limitations. performance limitations, and the conditions under which models may fail or degrade. This approach is especially relevant in countries where AI is already being deployed at scale in consumer finance. For example, Nigeria’s rapidly expanding digital lending ecosystem is now facing stronger consumer-protection rules that emphasize transparency and responsible conduct, creating an opening for the fintech sector to pioneer disclosure norms for AI-driven credit decisions

- Invest in Public Infrastructure: Rather than relying solely on proprietary platforms, Africa nations should build federated learning networks and regional compute clusters. This reduces dependence on foreign vendors and ensures data remains under African control.

- Center values rooted in African philosophies. Governance frameworks should not simply replicate EU or US models. Instead, they should articulate ethical frameworks grounded in Afro-centric philosophies such as Ujamaa, Harambee, and Ubuntu, which emphasize collective welfare, community responsibility, and consensus-based decision-making. This implies that AI systems should be assessed not only in terms of efficiency, but also in terms of their social impact—particularly on vulnerable populations—and their contribution to collective well-being.

CONCLUSION

Africa’s AI future will be determined by governance maturity, not just technological innovation. The continent can choose to become a testing ground for foreign systems or a co-author of its own regulation. The AU Continental Strategy and investments like Kenya’s billion-dollar commitment signal political will. Now comes the harder work: building the regulatory bodies, training the technicians, and establishing the accountability mechanisms that transform strategy into reality.

Africa’s technologists and policymakers have written the vision. Institutional implementation must follow.

Author Bio: Farah Abdou is a Lead Machine Learning Engineer and currently serves as an instructor, with expertise in responsible AI, multimodal AI systems, and AI policy. She holds certifications in Generative AI and large language model (LLM) customization and has published research on speech translation and AI ethics. Her work focuses on bridging industry–academic dialogue on ethical AI deployment in developing economies, particularly in African contexts.