Are Natural Resources a Curse or Blessing for Developing Countries in Africa?

A recurring theme when it comes to natural resources is their perception as curse or blessing for the countries that possess them. While some scholars argue that the discovery of natural resources is one of the key drivers of corruption and the weakening of democratic institutions, others even claim them as prerequisite for economic development.

Representatives of the dependency theories argue for the nationalisation of natural resources as a mandatory policy to achieve development. Modernisation theories are less deterministic and differentiate between wealth and development generated by resource extraction. However, some representatives of the latter even mentioned the extraction of natural resources as a prerequisite for his economic development (Rostow, 1960). Today, the idea of mineral resources as a precondition for development is highly challenged by the economic take-off of resource-poor Asian countries and the lack of economic development in resource-rich African countries. With many of the poorest African countries paradoxically also being some of the resource-richest, the narrative of the resource curse was born in the field of international development theory.

The Resource Curse

Among international development scholars, Sachs and Warner (1995) were the first ones to find empirical evidence for a negative statistical relationship between natural wealth and economic growth between 1971 and 1989, meaning that resource-rich countries were, oddly enough, less likely to experience successful development. Contradictory to previous predictions, resource-poor countries around East Asia experienced economic growth that quickly surpassed the one of resource-rich Africa or Latin America.

Building up on this revolutionary discovery, other scholars have discovered that only a fraction of the world’s resource-rich countries have managed to keep their GDP per capita growth rates higher than the 2.2% average of low-income countries (Gylfason, 2001). With the empirical evidence growing, the narrative of a resource curse spread among international development scholars. Reversing the initial theories, resource abundance was even considered the cause of poor economic development.

Nowadays, the relationship between natural resources and economic development is considered far more complex. While it is true that resource-rich countries, especially in Africa, have experienced lower development rates than their resource-poor neighbours, correlation does not automatically constitute causation. Furthermore, the African continent also witnessed examples of countries that transformed its resource wealth into successful development, or were initially trapped in the resource curse, but managed to escape it (Amundsen, 2017).

In 1994, among the top 15 countries with the highest per capita income, 5 were considered resource-rich (World Bank). In the case of Africa, prominent examples have also managed to transform their resource wealth into wealth and development of its people. Botswana’s transformation from one of the poorest countries in the world into an upper-middle-income country is directly related to the country’s discovery of diamonds (Hillbom, 2008).

The Resource Curse and its Effect on Democracy

When it comes to explanations why some countries are affected by the resource curse and some are not, there are three schools of thought: The cognitive explanation, the societal explanation, and the statist explanation.

First, representatives of the cognitive school of thought argue that policymakers in resource-rich countries experience a sort of myopia or strategic shortsightedness (Ross, 1999). With a steady inflow of governance revenue secured through resource-related taxes, policymakers have a lower incentive to develop strong economic policies (Wallich, 1960). Some scholars go as far as to argue that poor economic management even leads to policymakers significantly overestimating the longevity of natural resource wealth, leading to an increase in their government spending to an unsustainable amount (Manzano and Rigobon, 2001). Essentially, it perceives policy makers as lottery millionaires that instead of investing their money in a sustainable asset, assume the winnings will last forever. Countries that have experienced the resource curse are victim to bad policy making rather than the occurrence of resources (Townsend, 1995).

Second, the societal school of thought rejects the individual failures of policymakers and takes a deterministic approach towards the influence of private corporations. With the majority of tax revenue coming from one sector, the relevant sector can significantly influence policymaking, pressuring policymakers into economically bad decisions. While most societal theory scholars draw from examples from Latin America, Nigeria’s experience with Import Substitution Industrialization (ISI) policies and its failure to transition away from ISI has exacerbated the country’s dependency on oil (Auty, 1994). ISI is an economic strategy where a country aims to develop its national industries and reduce import dependence. However, once the country discovered significant oil resources, domestic supplies outcompeted international oil companies. Subsidising an already overly competitive supplier exacerbated the national industry’s dependence on domestic oil. This increased the oil companies’ influence to such a degree that they could influence decision-makers to not lift ISI policies, even though they were slowing down economic development in other sectors (Egwaikhide, 1997).

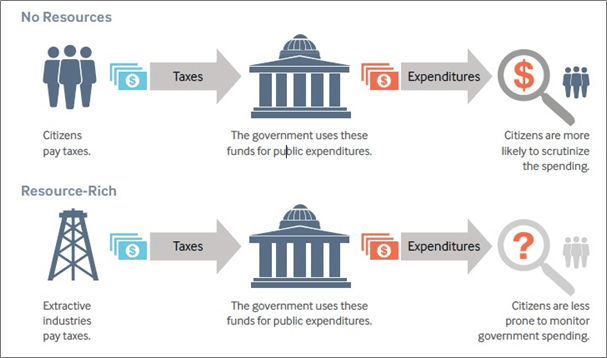

Finally, the statist school of thought is today’s most recognised explanation of the resource curse since it combines explanations from the cognitive and societal schools of thought. Most recognised is the idea of the rentier state, arguing that with a high percentage of the government budget deriving from resource rents in resource-rich countries, the government is less reliant on the collection of taxes from its citizens. In some cases, the discovery of natural resources has significantly affected the erosion of democratic institutions, the manifestation of authoritarian structures, or democratic backsliding. Generally, there seems to be a positive statistical relationship between the government’s responsiveness to it’s citizens and the government’s reliance on citizen taxation, making the democratic transition more likely in countries dependent on citizen taxation (NRGI, 2015).

Also, decision makers are also less involved in the needs and requests of its citizens if the government functions independent of them. Additionally, higher government control over natural resources tends to create a system of secrecy, which prevents accountability of financial mismanagement.

Figure 1: The Resource Curse on Democracy (Source: NRGI, 2015)

One African country that experienced almost a textbook example of the rentier state is Equatorial Guinea, a small nation in Central Africa. In the country’s pivotal moment in the 1990s, a discovery of substantial oil reserves promised transformative economic changes but paradoxically ended up damaging the country more than it benefited. Today, the country struggles with an economy heavily dependent on oil, making up a significant part of its GDP. While oil exports have fuelled an overall increase in GDP, the downside of overreliance on these natural resources has been the erosion of democratic institutions and an increase in authoritarianism (Sá and Rodrigues Sanches, 2021). Politically, Equatorial Guinea shares similarities with the theory, characterised by prolonged rule under President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo. With most of the oil resources laying in the hands of the president or his family, authoritarian governance and restricted political opposition have resulted in a lack of transparency and accountability, mirroring developments described by the rentier-state theory. Since the 1990s, the government has become less reliant on the taxation of its citizens. It could function based on resource taxation, making it less necessary to listen to political opposition. Thus, despite its oil wealth, the benefits have not been equitably distributed, leaving a significant portion of the population without tangible improvements in living standards or access to basic services (Sá and Rodrigues Sanches, 2021). Even though the overall GDP increased, so did inequality and economic dependency. Setting the country up for economic collapse once it runs out of natural resource revenue.

Everything was paired with an increase in corruption, particularly in the management of oil revenues, contributing to economic disparities. In essence, Equatorial Guinea’s experience very much reflects the complex dynamics of resource abundance and governance challenges witnessed in resource-rich African countries. While oil wealth has offered economic opportunities for some, the accompanying corruption, economic inequality, and rising authoritarianism underscore the necessity for mitigating policies and comprehensive strategies for sustainable development. However, these developments are in no means inevitable. Democratic backsliding can be prevented by effective governance, including increase citizen participation, transparency of government spending, and equitable distribution of wealth.

Conclusion

It is important to consider that a recurring feature of the resource course is that it is avoidable. All countries might experience some degree of negative consequences to resource wealth, but some seem to address them better than others. The differentiating factor between countries strongly affected by the ‘curse’ and countries that turned natural resource revenue into wealth and development is governance, particularly good governance (World Bank, 1992). In conclusion, the answer to whether natural resources are a curse or blessing for developing countries in Africa is complex. The resource curse narrative, as outlined by the rentier state, highlights the potential risks associated with discovering natural resources. Empirical evidence, particularly from resource-rich African countries like Equatorial Guinea, underscores the challenges of over-dependence on resource exports, which led to economic imbalances and democratic erosion. However, amidst these challenges, good governance emerges as the distinguishing factor. Some countries have successfully avoided democratic backsliding through effective policymaking. The resource curse is not an inevitable fate but a consequence of bad policy choices.